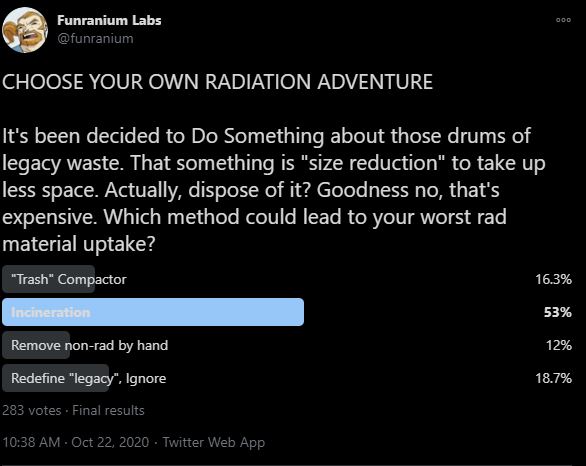

All of these choices technically cause legacy waste to take up less space, even if one is just a bullshit accounting trick. All of them have been tried, all of them have lead to uptakes, but like all of these quizzes my word choice is important. So, let’s define some terms.

[The fifteenth in an ongoing series of my compiled explainers for my CHOOSE YOUR OWN RADIATION ADVENTURE quizzes. There’s never really a right answer but some might work out better under the constraints of the scenario. It’s like poetry, really.]

I specifically asked for “worst rad material uptake”, not dose/exposure. Obviously, if you get a lot of radioactive material into the body there will be some internal dose from that. What I am not worried about in this quiz is external dose from the drums. It means these are the wrong containers for their contents, which isn’t out of the realm of possibility. A while back, I discussed transportation index and how it gets harder to ship the higher the gamma dose rate coming off the package. You don’t want SPICY drums because moving those around sucks. But the drums we’re considering aren’t going anywhere. This brings us to our next term: Legacy Waste

At a basic level, for all fields, legacy waste is the garbage that’s been sitting over there in the corner, that likely predates your predecessor in this job, and almost all documentation & institutional memory about it is gone other than “It’s bad and hard to deal with.” But for DOE, there’s a more specific definition bad enough that Legacy Waste gets capital letters. Legacy Waste is the garbage leftover from the early nuclear weapons program, where choices were made, at speed, with the conscious decision of “We’ll figure out how to deal with it later.” For DOE, Legacy Waste more or less means “Any nuke related waste that pre-dates the 1974 creation of the Energy Research and Development Administration taking over from the Atomic Energy Commission.” So, waste that dates roughly 1938 to 1974. This doesn’t just mean radioactive waste. The majority of the waste generated by the Manhattan Project and subsequent weapons program work wasn’t radioactive, but a lot of it was toxic. SEE ALSO: Basin F at Rocky Flats, formerly known as “The Most Toxic Square Mile On Earth”.

The mid-1970s were very important years in bureaucratic evolution and regulatory development. In the four years from 1974-78, not only did NRC and ERDA (which quickly became DOE) come into existence, but the recently created federal level EPA got most of the responsibilities they have today, including the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) which dictates how hazardous waste is handled and disposed of. Waste generated prior to RCRA might not be packed/stored properly. It might have incompatibles in the drum. It may have no documentation at all. And because those drums aren’t compliant and DOE has been ordered MANY TIMES to take care of all that shit that’s been lingering for decades, Things Must Be Done. Which is how we get to this quiz.

The easiest Legacy Waste to take care of is that which you have some idea of what’s in the drums. Enough that you can just slap some new labels on, declare that this is now typified and no longer Legacy Waste. High fives all around, it’s Miller Time! Everything’s cool, right? The level of coolness is a function of how much you trust what information you have. As an example, Glenn Seaborg’s lab notebooks are immaculate, clear and easy to follow. Seriously, I’m jealous of his penmanship. While they are very trustworthy for process, they are absolute pants for trying to figure out his waste. Documentation from ye olden nukes tend to be, to put it kindly, results oriented. The waste was something of an afterthought. Garbage cans were things for janitors to worry about (SEE ALSO: various contaminated landfills). But even the Bob B. Dobbs impersonating BOLD MEN OF ATOMIC SCIENCE recognized that some of the waste they made couldn’t just be thrown away willy nilly and tossed it in drums instead…a minimum of 45 years ago. Drums are not immortal, especially when filled with nasty things. You just kicked the can, uhh, drum down the road.

You aren’t likely to have any materials uptake from just applying a new label. But some unlucky bastard will be the one that has the drum fall apart on them. Or finds a puddle on the floor from the bottom that’s rusted out. Then you get to do a clean up which generates more waste drums than the original drums, but at least you know what it is now and it isn’t Legacy Waste. MISSION ACCOMPLISHED!

For our next vocabulary word, we have the waste treatment concept of “size reduction”. When wrangling waste, you have some options of how to process it to reduce toxicity and/or costs. Taking up less room in the landfill which charges by the cubic foot is absolutely essential. The people tossing things in drums back in the 1940s did things like throw One [1] Radioactive Tumbleweed in a 55gal drum and then put it behind a building to forget about for the next 60 years. So, yeah, there’s a lot of good and necessary size reduction you can do here.

This brings us to methodology. Most of you decided that an incinerator is a terrible idea likely to lead to radioactive materials uptake by a large downwind population because, well, that’s happened and it’s why we don’t have many of them anymore. Because a waste incinerator with no filters, no scrubbers, NOTHING, is no better than a burn pit that just happens to have a chimney to insure good lofting of materials. Proper waste incinerators let very little out the stack at all and leave you nicely concentrated radioactive ash and scale, which you then have to clean out and drum again, but you might have condensed 12 drums worth of Legacy Waste condensed down to one Ashy Boi. Nice!

For the workers that have to deal with that, the airborne contamination hazard of cleaning the incinerator is serious business. You only reduced the bulk of the drum contents, you didn’t make them any less radioactive. You also made them easily airborne as ash. Also, wouldn’t think I’d have to say this, but no matter how good your stack is, incineration is a terrible idea for tritium contaminated waste. On a positive note, the release limits for tritium are incredibly high, but you won’t make any friends in the neighboring communities.

So, if you can’t burn it, you can compact it. Just like any other trash compactor, we can try to squeeze any extra space out the drum by crushing the contents as small as possible. You could crush the entire drum, contents and all, but I don’t recommend that. You put the drum in the EXTREMELEY WELL VENTILATED compactor, take the lid off, and then let the crushing piston down to do the squishing, and this part is very important, in the drum. Don’t take things out and crush them elsewhere.

This is when you discover if there was anything breakable in the drum that contained nasty things. Or perhaps something pointy that now goes through the side of the drum with a poof of contamination into the air. Hopefully the air handling can cope with that. Drum compaction is a lottery except all the lights and sirens going off aren’t a jackpot, it’s a CAM alarm.

“Now Phil” you say, “Hitting surprises in the drum seems very careless. Didn’t you x-ray this thing first?” Of course we do, but an x-ray can only tell you so much as to what the contents actually are. It should, however, reveal things that should give you pause. A lot of things “should” happen. But what does happen is these compactors get shut down for decon, often for months or years and that the workers operating them usually end up get a snootful of something.

To avoid the problem of such surprises, we get to opening and manually sorting drum contents by hand. Digging through Legacy Waste drums is, hands down, my absolute least favorite thing about my profession and the thing that got me closest to quitting. That preliminary x-ray can only tell you so much about the items in there. Like that there’s a mostly empty can with some liquid in it. It cannot tell you that the drum is slightly pressurized from the volatilized organic compound in there and is going to give you a contamination burp on opening. It usually can’t reveal all the broken glass in there. It doesn’t tell you how everything is mercury contaminated in addition to radioactive, which means GODDAMMIT this is all MIXED Legacy Waste.

Honestly, most of it is mixed waste which is why no one wants to touch it. :(

Short of putting it into a glovebox to work on, no one is happy to crack open a drum and rummaging around in it because the potential for personnel contamination with unknowns is so high. Even in a glovebox, contaminated sharps will get you right through your shielded glove. While incineration and compaction may lead to releases with uptake by workers or the public, their engineering controls make it likely that the uptakes will be comparatively small for any one individual.

Drum sorting has a much higher chance for a significant individual uptake.

In the events the inspired this, there was a Legacy Waste drum that was chosen to be hand processed due to its weird Co-60 gamma spec signature and higher dose rate than the rest of the drums. With a circa 1950 vintage, any appreciable Co-60 made little sense. The drum got cracked open. As per what seemed usual, there was a burp which than caused the Continuous Air Monitor (CAM) alarm to go off. After everyone evacuated, surveyed themselves for contamination, and found themselves to be clean, they got back in there to start unpacking.

What was in the drum is what is in most drums: contaminated PPE, much like the workers were making more of right now. Contaminated PPE is good because it’s compressible & combustible. Easy to size reduce. There were some other fiddly bits in there and an armadillo skeleton. What was not in the drum, however, was anything that which had an appreciable Co-60 signature. PPE was covered in actinide fun, but no Co-60.

That’s when they took a really hard look at the drum itself.

If Co-60 waste had been placed in the drum around 1950, it should have all decayed away by the 2000s. But if the drum itself had somehow been activated, it could have grown it’s own Co-60.

At some point in this Legacy Waste drum’s life, it got put somewhere that it really shouldn’t. Best guess is that at the drum got to live in/near an accelerator facility where the shielding wasn’t quite up to snuff. Or, at the very least, it was there long enough to grow enough Co-60 to notice.

Drum stopped being Legacy Waste and got a new drum of its own.

~fin~

PS – If you’d like to know more about properly taking care of waste, including your many options to deal with it, allow me to give you the Follow Friday recommendation of @nuclearkatie. She may not make you feel any better about things however.