GOOD NEWS: when McMansions attack they bring some support networks with them.

BAD NEWS: not *enough* support network, because one of the reasons to move to the sticks is to avoid taxes which would pay for that support, so…bummer.

But there was a good thing to really help under resourced jurisdictions that grew out of the catastrophe of the 1991 Oakland Hills Fire: the birth of the Mutual Aid System. READ: when you call for help, people will come, and everyone will use the same jargon, clear speech, and radio frequencies (except NYC). This was also the birth of Unified Incident Command. Everyone in America, except NYC, got the message that it’s nice when you can count on your neighboring agencies to help you in a pinch. Outside agencies trying to help NYC with 9/11 had a really hard time because NYC alone hadn’t got with the program, which was one of the many findings of the 9/11 Commission. NYPD could barely talk amongst themselves, much less coordinate with NYFD. Trying to undo NYC’s “The New York way is the best way and fuck you” attitude for just emergency response was one small part of creating the Department of Homeland Security. You know, so we can learn how NYC wants to do things and make sure the rest of the country does that too.

But I digress.

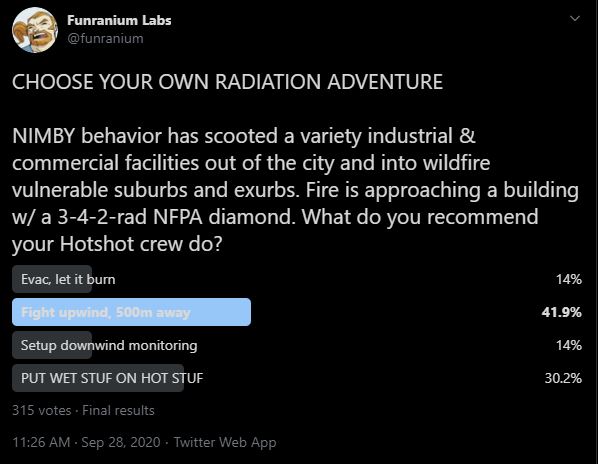

In the American West, one of the most deployed groups under Mutual Aid are the hotshot teams, AKA professional wildland firefighting crews that are usually the very first backup that arrives to a wildfire that’s exceeded the locals’ capacity to fight. What your hotshots can do is very dependent on how fast the wildfire is moving, terrain, and what they have time to set up before it’s too late. Your hotshots see that NFPA diamond and call because they want a little more guidance than “PROTECT BUILDING”. People did a close read of the NFPA diamond primer I shared, but missed some close reading of the listings where those are *examples* of behavior. A Yellow 2 (reactivity) does not guarantee water incompatibility. If that was the case, you’d get this down in the white section.

And while these quizzes seem to prime and attract people who are frightened/intrigued by radiation hazards, let me assure you that there is nothing that a firefighter wants to see less than that W. They don’t like rad, but they HATE “no water”. To quote my old Santa Clara County Fire instructor, Cap’n Bubba, if you cannot put the wet stuff on the hot stuff until it is cold stuff and this does not compute to the firefighter mind. (Cap’n Bubba was a very bright hazmat guy but liked to play dumb hosedragger.)

But back to the NFPA diamond, of the 3-4-2-rad, the Yellow 2 is the least concerning. The rad trefoil down in Other Information will give most firefighters pause but it’s nowhere near as terrifying as the Blue 4. That tells the team there is either a prompt death or a fast cancer. This is where I get to share one of my favorite acronyms from the field of Industrial Hygiene to describe what a facility with a Blue 4 is when it’s on fire. IDLH: Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health.

Remember, the NFPA diamond is telling you about the hazards of the contents this building *WHEN IT IS ON FIRE*. For example, the dumpster fires behind Silicon Valley chip fabs in the 1970s where you suddenly have an entire engine crew dead of interesting cancers within 6mo (yes, this happened). Funny enough, things we normally would be day-to-day very worried about working with for their carcinogenicity, like asbestos or beryllium, would hardly count on the NFPA diamond during a fire. For that matter, radioactive materials don’t get more radioactive because you light them on fire, but you might make a larger mess. This is why they’re down in “Other Information”. You need the other three to know how bad things are as you approach and the white diamond is just Challenge Score Multiplier.

They aren’t gonna set up downwind monitoring because they have much more important things to do with chainsaws. Notify the EPA or local equivalent to get things started on that. For that matter, there may be no wet stuff to put on hot stuff here. Generally speaking, there’s gonna be hookups at somewhere on the site for them to run hoses to but if that’s not in a strategically safe space or the water supply is gone then the hotshots do what they do best: chainsaws, backburns, and trenching. If the circumstances are kind enough to make the protective lines to keep the fire from getting to the building, stay upwind and at good distance following the rule of thumb: stick your arm out, stick up your thumb, and if that covers the entire incident, you are far enough away.

When the emergency alert went out, I happened to be nearby and went to go see what was up as the call was for a building I kinda took care of when other people went on vacation. Lo and behold, the fire crew I’d recently trained was at the end of the block from the building, standing around the truck in turnouts, as a small plume of smoke rose from the building.

Me: What the fuck are you standing here for?

Captain: The building has rad on the diamond.

Me: So?

Captain: We can’t hose that down.

Me: If you don’t there won’t be a building anymore. The latency of hard body radiogenic cancers are about 40 years. The latency on that fire is minutes.

Captain: But the contamination…

Me: I CAN CLEAN CONTAMINATION! THAT’S MY FUCKING JOB! It’s expensive, it takes a long time, but I can’t unburn a building. Use your fucking meters like I trained you and put the fucking fire out.

[firefighters scurry]

When I shared this story with Cap’n Bubba later, I thought he was gonna to wet his alligator skin cowboy boots from laughing so hard. He complimented me on my understanding of firefighter mindset and creative use of motivational swearing.

Incidentally, the building was fine.

~fin~

MORAL: The real lesson of this thread, and that my firefighters need to take to heart, is not getting fixated when assessing the Immediacy of Hazards. In the event of fire, FIRE is the most immediate concern. You can worry about radiation releases/exposures when you aren’t burning.